Walk into almost any law firm right now, and you’ll hear the same mix of excitement and caution about AI in law firms.

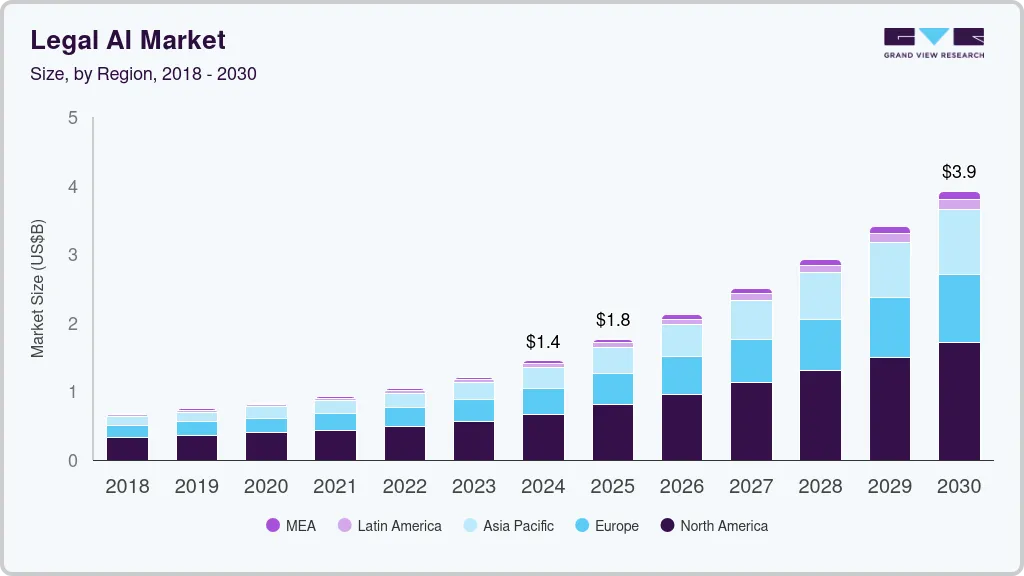

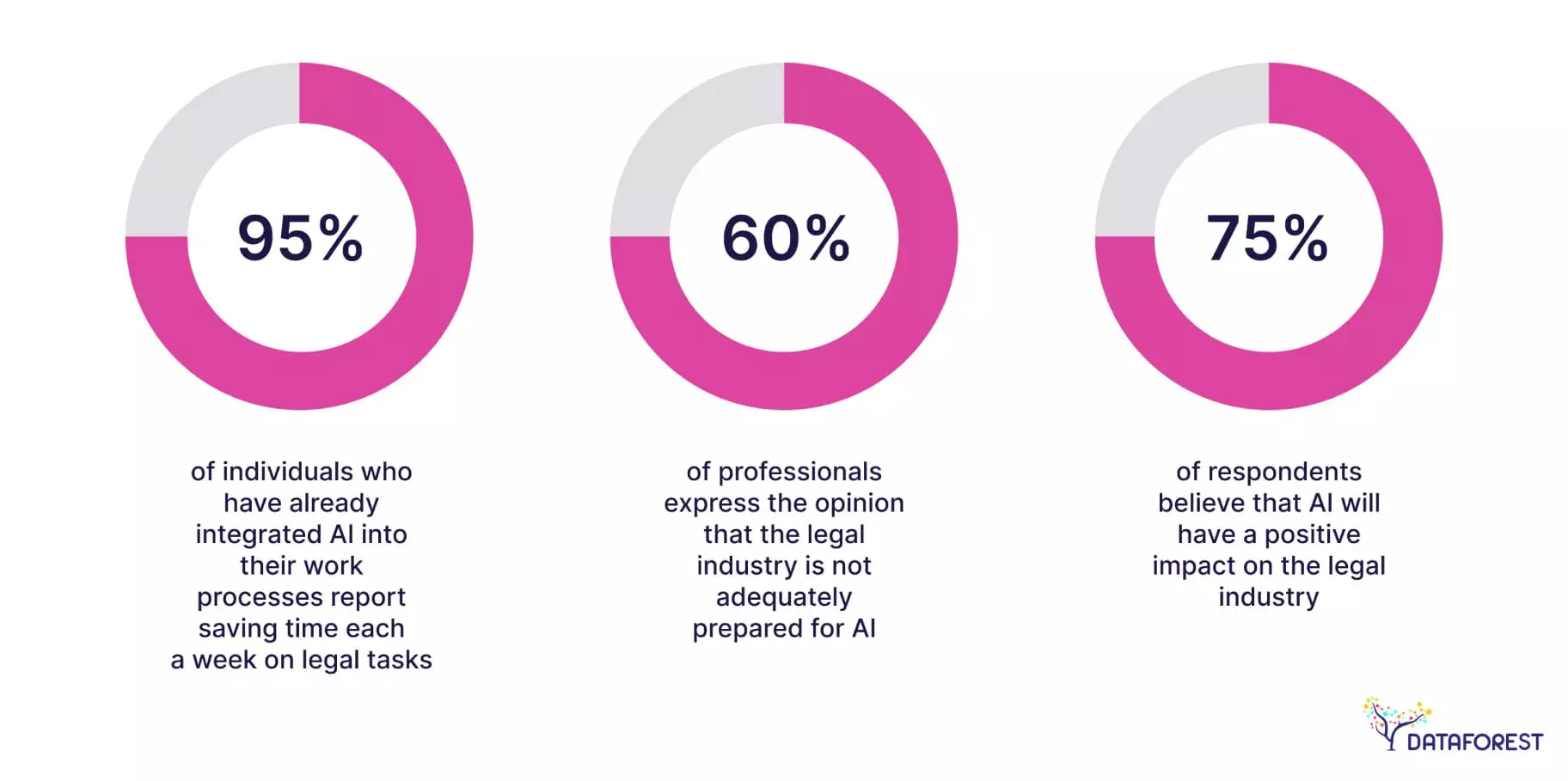

The tools have moved fast. In just a couple of years, large language models stopped being curiosities and started showing up in legal research, contract review, and client intake. The AI market for legal professionals is on the rise, as you can see below.

They’re reshaping the workday in ways that feel very real, but there’s still some uncertainty on how far it can go, or should go, when it comes to automating work.

This piece digs into what AI is genuinely good at in law firms in 2026, where it still falls short, and how to steer your practice without putting clients or ethics at risk.

The Evolution of AI in the Legal Field

AI in law started as a way to get through document review faster.

Early e-discovery tools helped sort emails and flag relevant material.

Courts began accepting predictive coding around 2012, which made firms more comfortable using it at scale. At that point, AI wasn’t “intelligent” in the way people use the word now. It was practical, reduced hours, and cost. That was enough.

Then the tools improved.

Instead of just sorting documents, systems began identifying clauses, grouping similar language, flagging inconsistencies, and spotting patterns across large contract sets. That’s when AI moved from being a back-office efficiency tool to something closer to analytical support.

Around the same time, legal prediction research gained attention. A widely cited study suggested that a machine-learning model could work over a long historical dataset.

That didn’t mean machines were replacing judges. It meant that patterns in judicial behavior could be modeled. For firms that opened up conversations about litigation strategy and risk assessment in a more data-informed way.

Then generative AI changed the tone of the conversation.

With the release of GPT-4 in 2023, and strong performance on standardized tests like the Uniform Bar Exam, it became clear that AI could do more than classify and predict. It could draft, summarize, and structure arguments. Not perfectly, and not without oversight, but at a level that made it useful in daily workflows.

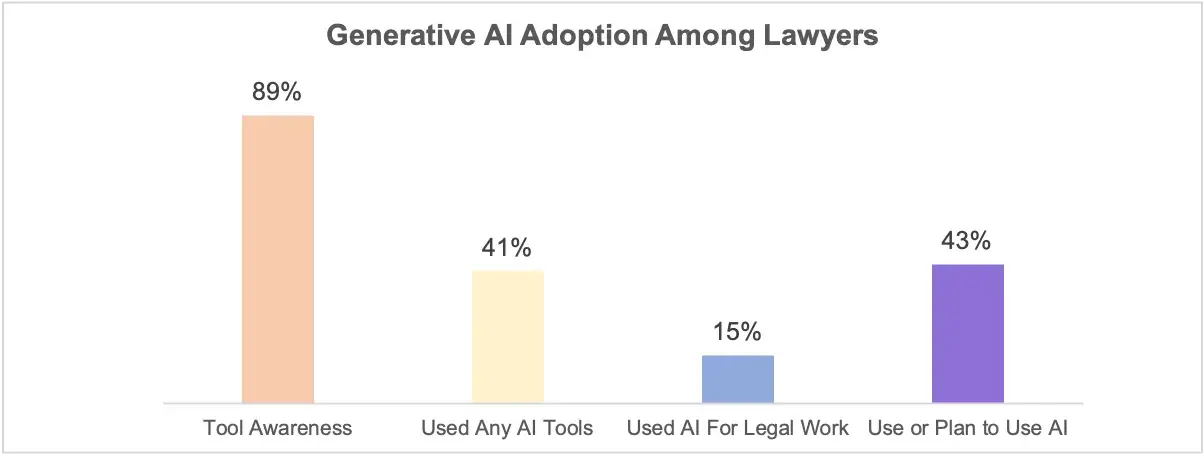

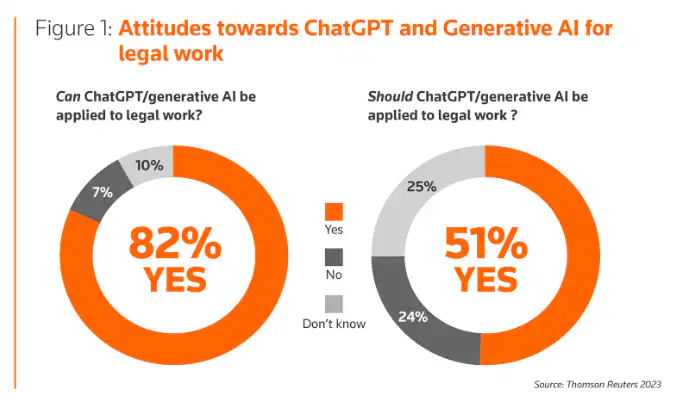

That shift lowered the barrier to entry. You didn’t need a data team. Any lawyer could test it directly, and they did, as you can see below.

Tom Rockwell, CEO of Concrete Tools Direct, runs a business where operational reliability directly affects margins.

Rockwell says, “In our company, you don’t introduce new equipment across every jobsite overnight. You test it in real conditions, see what holds up, and expand from there. AI should be treated the same way. Start where the bottleneck is, measure the improvement, and scale what works.”

So the progression looks something like this:

- First: document review and e-discovery automation

- Then: clause detection, issue classification, outcome modeling

- Now: drafting assistance, summarization, and reasoning support

The core idea hasn’t changed. AI handles pattern-heavy, repeatable cognitive tasks. Lawyers still handle judgment, context, negotiation, and accountability.

Opportunities Offered by AI for Law Firms

AI works best in law when it takes on repeatable, data-heavy work so attorneys can focus on judgment, negotiation, and strategy.

- Document-heavy work gets faster. Think bulk NDAs, vendor contracts, or classifying large datasets in investigations. Well-implemented AI can sort, summarize, and surface the 10% that deserves human eyes. Automation helps with contract analysis and data entry, but mainly it’s about getting attorneys out of the weeds.

- Legal research has more depth, faster. Retrieval‑augmented systems can pull from caselaw, regulations, and your internal memos to produce starting points that feel like you already had a first‑year associate on it, though you still need to validate everything. Advanced AI tools save time and resources while offering comprehensive research capabilities.

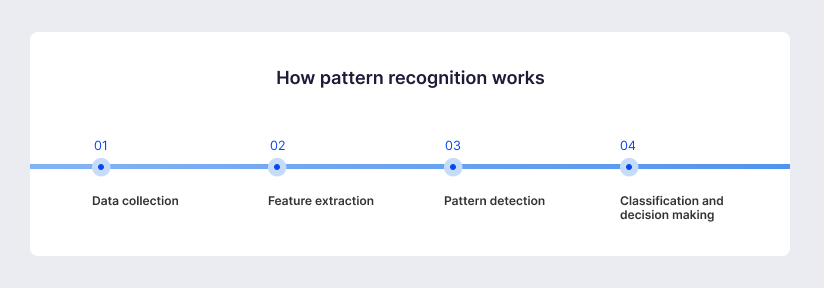

Pattern recognition sharpens strategy. No model replaces instincts at a settlement table, but pattern recognition on venues, judges, and motion histories can inform decisions. Evidence from academia and legal tech pilots suggests a useful signal when used alongside attorney judgment.

- Client interaction improves. Chatbots and AI-driven systems handle guided intake and create plain‑language summaries of next steps. Firms are trimming response times and setting clearer expectations, for many clients, that’s half the battle in feeling cared for.

Ryan Walton, Program Ambassador of The Anonymous Project, works with people navigating complex emotional and institutional systems where clarity and trust matter.

Walton says, “In high-stress situations, most people aren’t asking for perfect legal theory. They’re asking to understand what’s happening and what comes next. If AI helps firms respond faster and translate complex steps into plain language, that reduces anxiety immediately. But it can’t replace empathy. Clients still need to feel like a person is accountable for their case.”

Point these tools at the right problems, and the lift is obvious.

Limitations and Challenges Facing AI in Legal Practice

Law isn’t a low-stakes industry. Mistakes are expensive, reputational, and sometimes disciplinary. So when AI enters the picture, it doesn’t just add capability. It adds exposure.

The first friction point is ethics. That’s why the NIST AI Risk Management Framework keeps coming up in conversations. They give structure on how to identify risk, test performance, document controls, and assign responsibility. In a regulated profession, structure lowers anxiety.

Regulation itself is also tightening.

The EU AI Act introduced a risk-based approach to AI systems.

In the U.S., the American Bar Association has long emphasized technological competence under Model Rule 1.1. In England and Wales, the Solicitors Regulation Authority has issued guidance on AI use and client protection. None of these bans AI. But it does make clear that “we didn’t know” won’t be a sufficient defense.

Then there’s the practical issue everyone quietly tests for: accuracy.

Hallucinated citations happen. Overconfident summaries happen. The system can sound certain while being wrong. That’s not a minor flaw in legal work. Human review remains mandatory. Retrieval grounding helps. Testing against real firm matters helps. But the risk doesn’t go to zero.

Our guide on editing AI content helps with this.

In high-stakes matters such as medical negligence, where documentation, timelines, and causation analysis are central to the case, even small factual errors can have serious consequences.

AI can assist with summarizing records or organizing evidence, but it cannot replace careful legal scrutiny. In these areas, accuracy directly affects outcomes, liability, and client trust.

Ryan Beattie, Director of Business Development at UK SARMs, operates in a consumer market where trust is fragile, and misinformation spreads quickly.

Beattie says, “We’ve learned that confidence without accuracy damages trust fast. If a system sounds authoritative but gets a detail wrong, customers don’t blame the tool. They blame you. In law, that’s amplified. AI can accelerate work, but firms have to verify every claim like it came from a junior associate. Speed never outweighs credibility.”

Cost is another constraint people don’t always discuss openly.

Licenses are one part. Integration is another. Connecting AI to a document management system, cleaning internal data, running pilots, training staff, updating policies—none of that is free. Modular, API-driven tools and secure cloud environments have lowered the barrier for experimentation. But scaling across a firm still requires budget and internal buy-in.

Firms that treat it like a powerful assistant with supervision, guardrails, and measurement tend to navigate the risks better than those treating it as either a silver bullet or a threat to avoid entirely.

Preparing for the Future: Strategies for Law Firms

Lawyers don’t trust tools they don’t understand. When they do, they’re far more comfortable using it without outsourcing judgment.

That doesn’t mean everyone needs to become technical. It means role-based learning. Partners don’t need the same depth as associates. Litigation teams don’t need the same examples as transactional groups.

Some firms are setting up sandbox environments so lawyers can experiment without risk. Others appoint internal “AI champions” who test tools, write short playbooks, and host informal office hours. Nothing fancy. Just visible internal ownership.

Then there’s the question of where to start.

A short, living policy is more useful than a dense memo no one reads. Cover approved use cases. Clarify what data can and can’t be entered. Set expectations around client consent where appropriate. Define when human review is mandatory. Spell out what happens if something goes wrong.

But the real work is embedding it into daily workflows, things like mandatory citation checks, disclosure language where required, and periodic testing for bias or failure modes.

A few practical lessons keep surfacing:

- Treat prompts like instructions to a junior associate. Be specific. Provide context. Ask for sources.

- Clean your knowledge base before connecting it to AI. Duplicate or outdated documents will surface just as quickly as good ones.

- Measure what matters. Track time saved, error rates, client feedback, and attorney adoption before deciding what to scale.

The firms that benefit are adjusting one workflow at a time, not attempting a complete overhaul at once.

If you’re experimenting with AI tools in your own workflows, it’s worth exploring platforms like Writecream to see how drafting, summarization, and structured content generation actually behave in practice.